The Many Faces of Policing

Derek Chauvin wasn’t the first. While law enforcement has shapeshifted over time, racial injustice and police violence have been around for 400 years. Meet the previous enforcers of brutality.

400 Years of American Policing

1600S: SLAVE OWNERS AND WATCHMEN

While slave traders and owners enforced brutality in the 1600s, America also established neighborhood guards. Inspired by the British, watchmen were the country's first approach to public safety. Boston and New Amsterdam (New York City) were among the first cities to adopt this system, where squadrons of paid and unpaid locals kept the peace and performed informal public safety duties.

Sources: History of Policing, Law Enforcement Museum, Time Magazine

1700s: SLAVE PATROLS

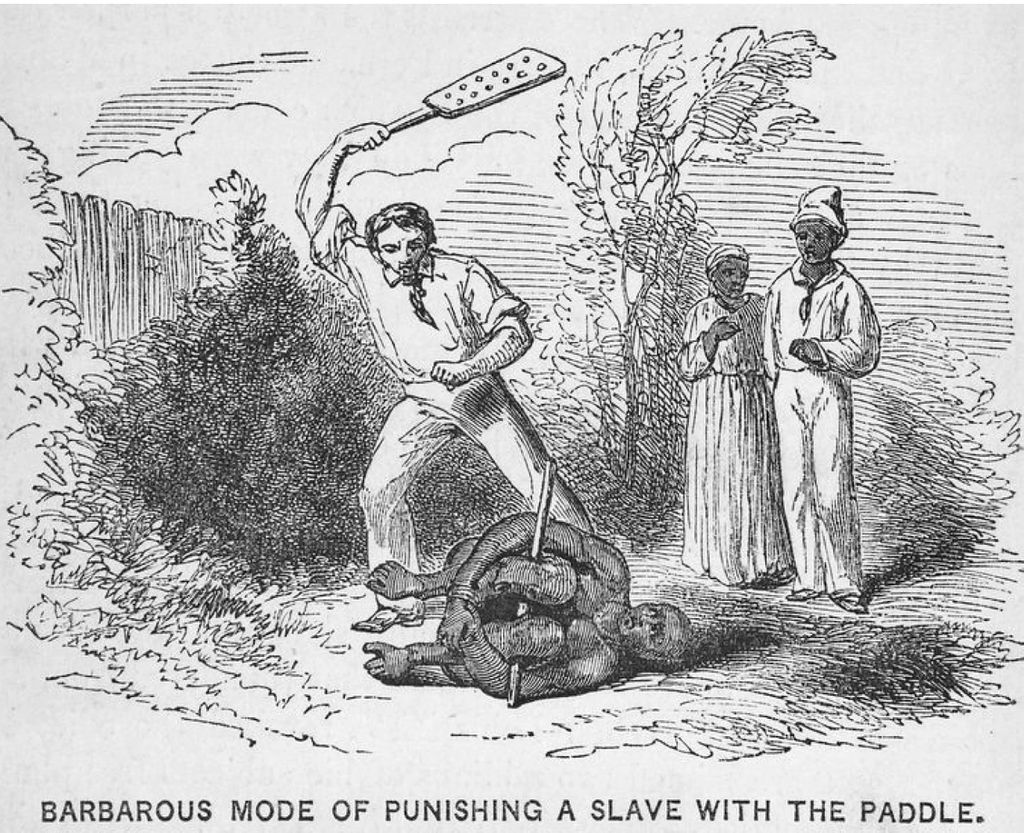

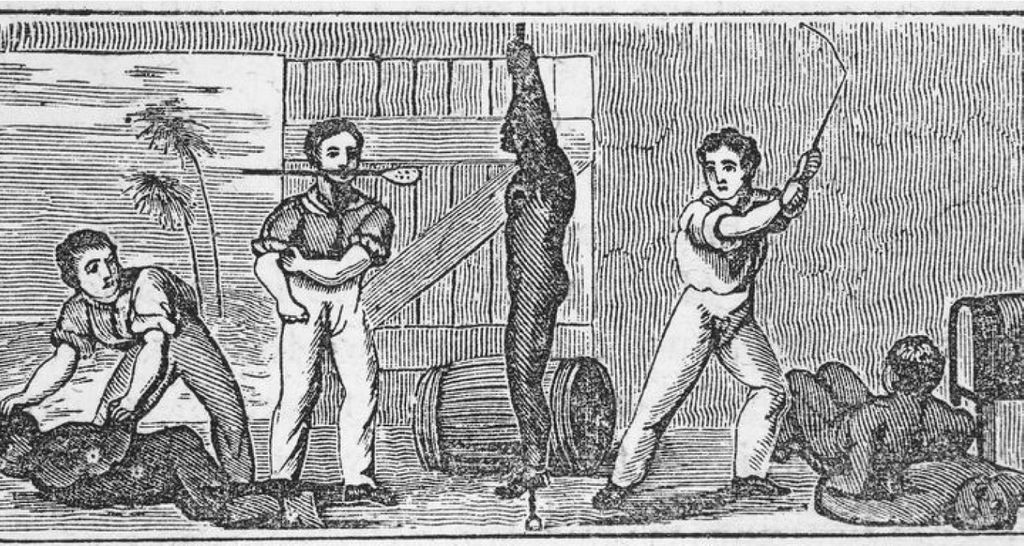

Formed in South Carolina, patrols were state-mandated groups tasked with beating and arresting any slave who breached the slave code laws (more on that later). Their role was to discipline the enslaved, catch runaways, and create organized terror to dissuade revolts. All white men ages 21-45 had to participate, whether or not they owned slaves or worked on a plantation. The patrols existed for over 150 years.

The history of police work in the South grows out of this early fascination, by white patrollers, with what African American slaves were doing. Most law enforcement was, by definition, white patrolmen watching, catching, or beating black slaves.

Source: Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas

1800s: SOUTHERN Vigilantes

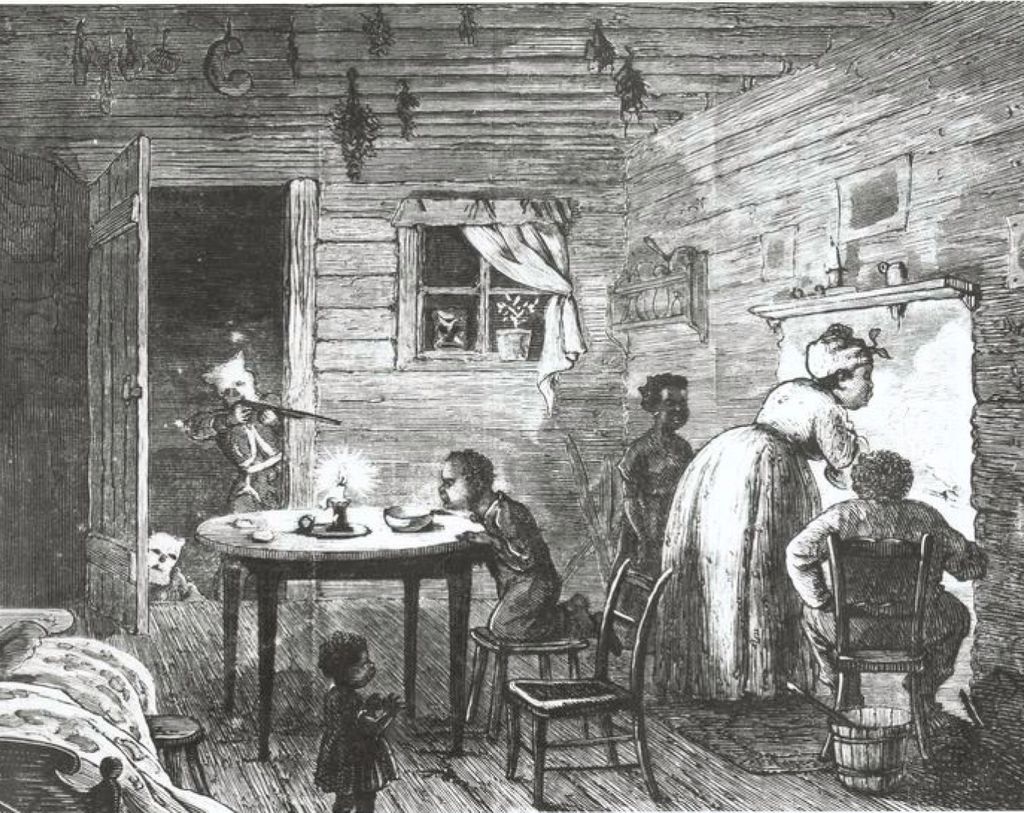

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. While it declared freedom for enslaved people in certain states, 200 years of fear, violence, and oppression didn’t suddenly vanish in a day. White citizens began organizing their own protection.

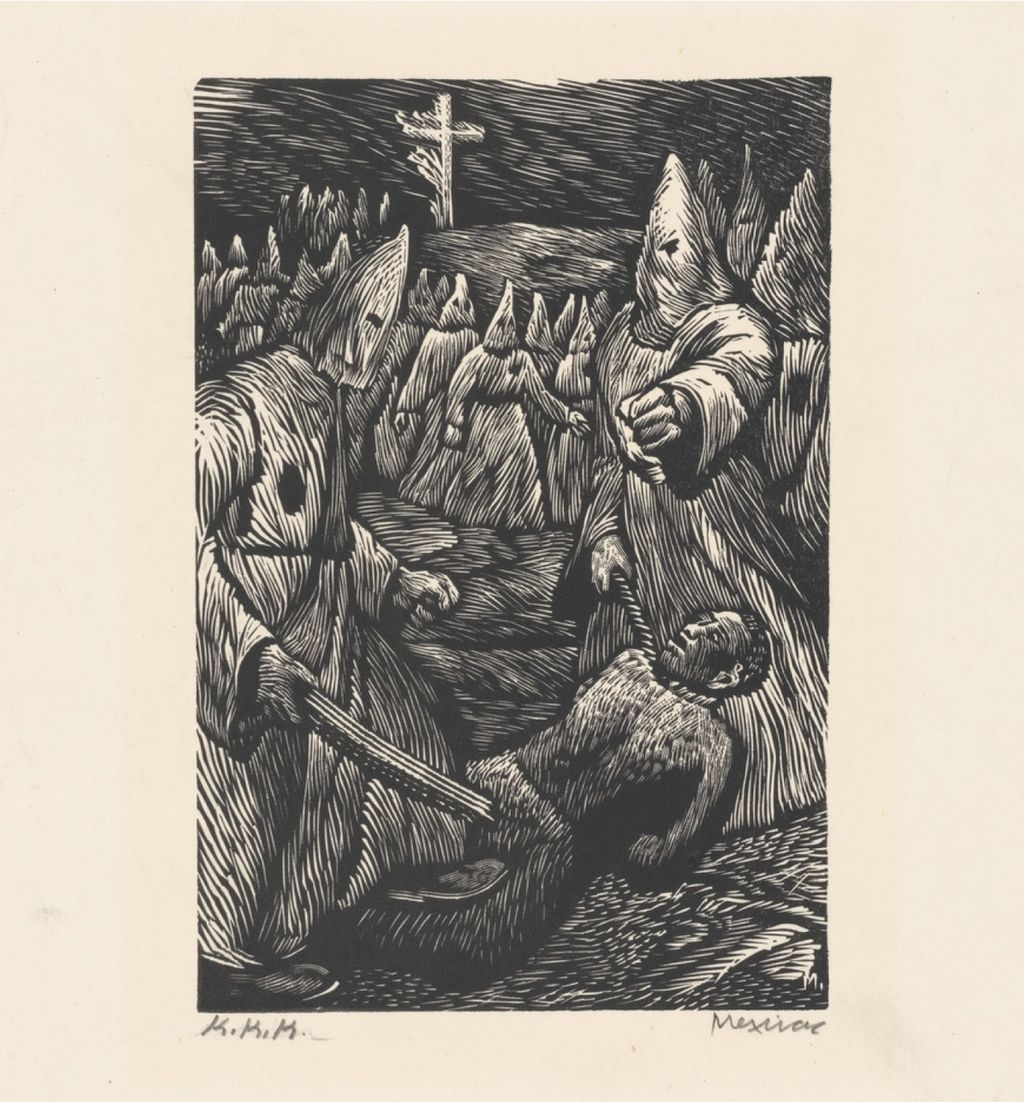

Enter the Ku Klux Klan.

It's homegrown American terrorism. They probably killed more Americans than Osama Bin Laden did.

Source: PBS

The Klan kicked off an underground campaign of violence against Black people, white activists, and Republican leaders to reverse the progress on Black equity. The Klan was only one of several white supremacist groups that emerged during this era.

3,446 lynchings

EARLY 1900s: THE FORMAL POLICING

While vigilantes policed the south, the north had a different strategy. Boston and New York were the birthplaces of the modern police force. This was the first time the cost of policing was taken on by citizens. Police wore uniforms, adopted a militaristic approach, and started to become more visible in local communities (early beat cops). They used Black codes and Jim Crow laws to control freed Black populations who were working in the agricultural caste system.

This system of essentially tracking Black people’s movements to control them needed a similar armed and/or empowered law enforcement constituency.

Source: NPR podcast and article

LATE 1900s: Deputized Political Muscle

The relationship between policing and politicians became tighter in the 1900s. Politicians helped hire police chiefs and officers, and police helped politicians stay in power by enforcing policies of control and violence under the cloak of protection. Police also engaged in election fraud and solicitation. Accepting bribes was normal.

Upon being hired, policemen were also expected to contribute a portion of their salary to support the dominant political party. Political bosses had control over nearly every position within police agencies during this era.

This became so common that a whole police force would change when there was a new political administration in power.

How police corruption evolved into sanctioned violence

To get away from harsh segregationist laws and find better job opportunities, Black Americans started to move north in the early 1900s—the Great Migration. Tensions rose as Black people moved into the same neighborhoods and applied for the same jobs as white people. This led to a series of 150 riots and disorders, started by white racism, that broke out in cities across the country and left Black communities devastated.

Police routinely protected and supported white mob violence against Black people. Some local police departments even actively participated in the riots. Black homes, churches, and schools were looted and torched. Blacks were stoned, lynched, and burned.

When police officers had the choice to protect black people from white mob violence, they chose to either aid and abet white mobs or to disarm black people or to arrest them.

Source: NPR

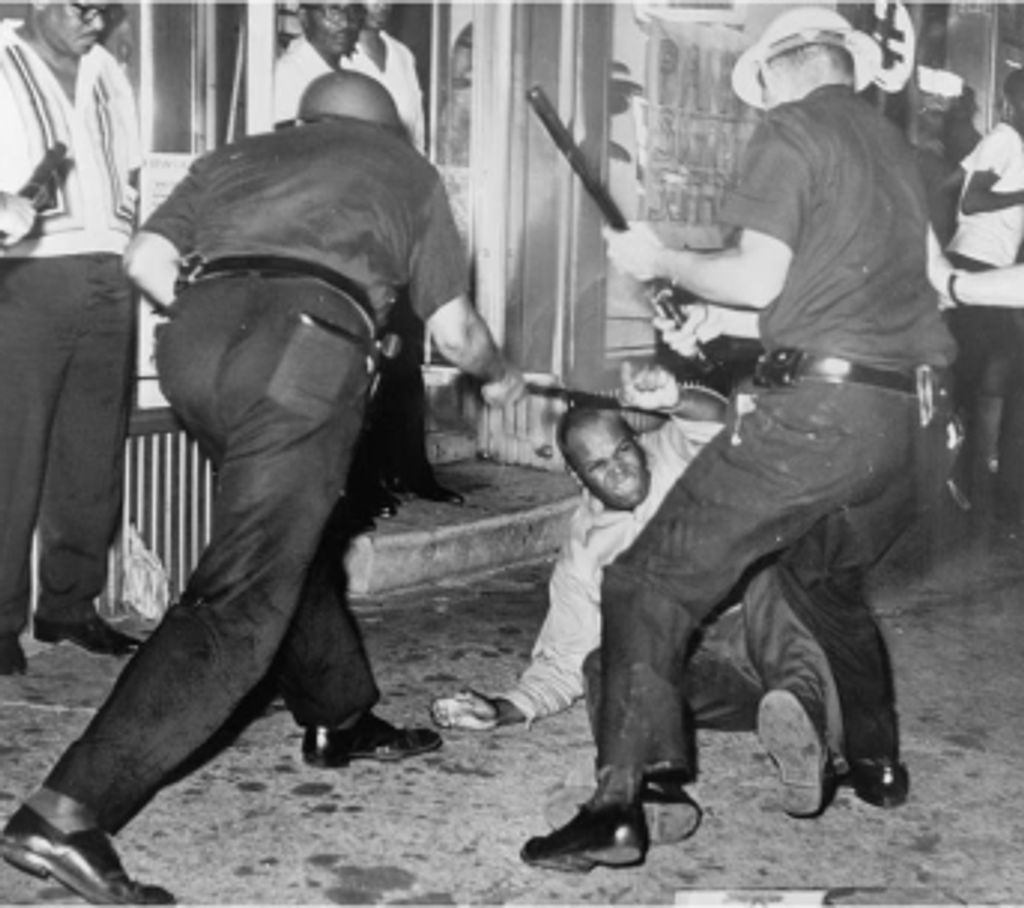

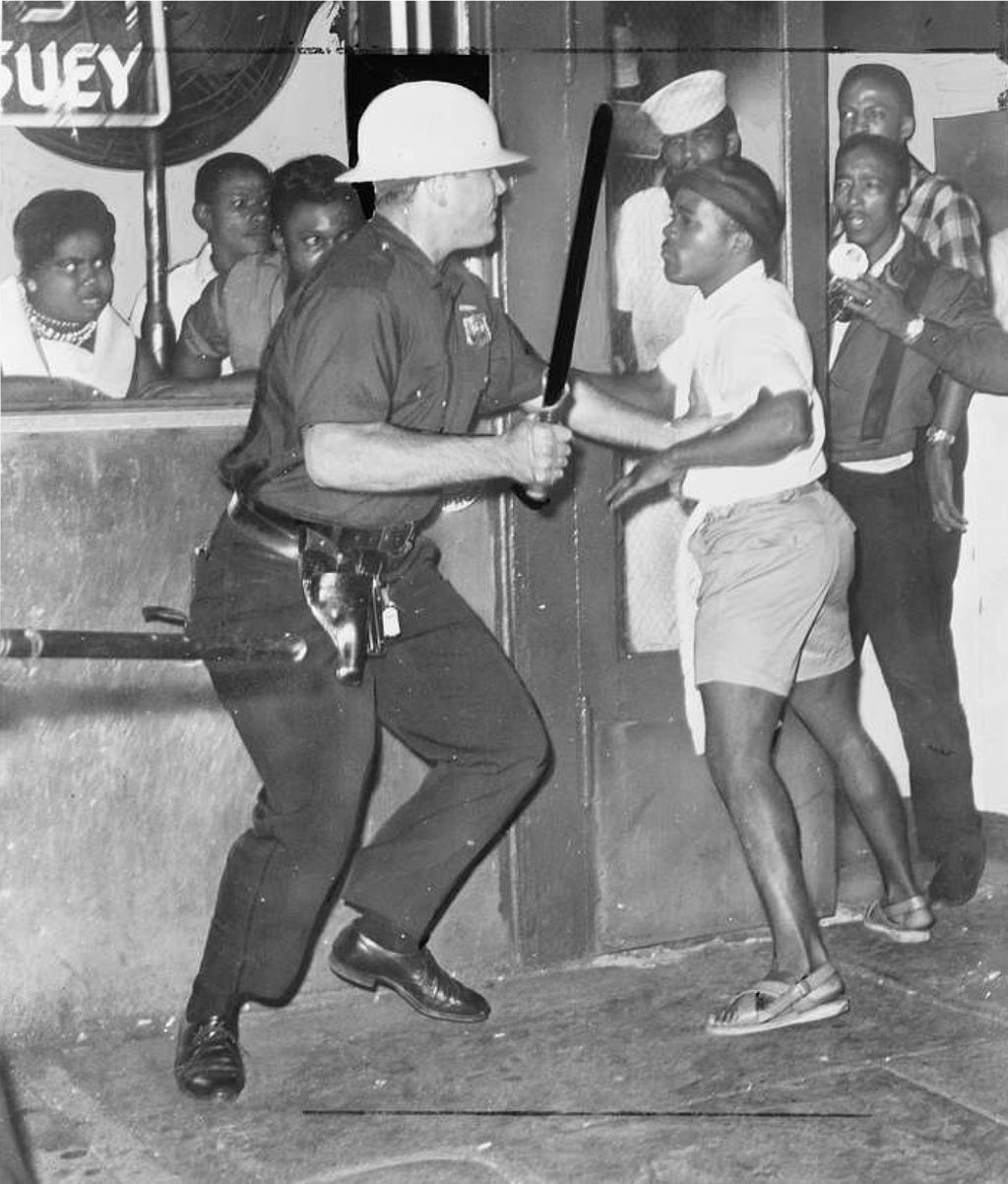

In the late 1950s and 60s civil rights protests, marches, and riots were openly met with aggressive use of force by law enforcement. This led to the public acknowledgment from the government in the Kearner Commission Report that police action invariably seemed to cause and ignite public disorder.

A few examples: The Bloody Sunday protest for voting rights (1965), the execution of Fred Hampton with 90 bullets (1969), and the MOVE bombing by the Philadelphia police (1985).

Initiatives like Nixon’s “War on Drugs” campaign in 1971 justified using force in policing the Black community, and the general public accepted it.

The 2000s: A Militarized Police Force

We’ve now seen how former slave owners, police officers, politicians, individual citizens, prison wardens, and even sitting presidents have played a role in enforcing systemic racial brutality.

In 2020, these factors haven’t changed. In fact, the network has exploded at a local level to include district attorneys, mayors, city council members, police chiefs, and police unions. While some of these players are bold about their support of the current system, like police unions, others quietly show their support to maintain the status quo or advance their careers.

In this final section, we’ll dive into two major trends that help define 2000s policing: mass incarceration and militarization.

Mass Incarceration

The U.S. has 5% of the world’s population and 25% of the world prisoners, more prisoners than soldiers, more correction officers than marines, more prisons than Walmarts.

Today we still see the impact of Nixon-era policing policies through mass-incarceration.

“Resisting arrest” is arbitrarily defined and routinely used to criminalize Black people who are more likely than white Americans to be arrested and convicted. Sentencing policies, implicit racial bias, and socioeconomic inequality contribute to racial disparities at every level of the criminal justice system. Today, people of color make up 37% of the U.S. population but 67% of the prison population (Note: we generally prefer to distinguish Black from the term "people of color," however this stat represents both communities). In 2014 alone, private prisons made $629 million in profit.

Critics argue that mass incarceration parallels the physical segregation of the 19 and 20th centuries. It strips citizens of their right to vote to improve the policies that create inequality in policing. Police unions aggravate the problem by drafting contracts that make it harder for officers to be held accountable.

Police Militarization

When law enforcement killed unarmed Black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, the militarization of police was propelled to the national stage. Americans discovered that equipment more commonly used on battlefields, like flash-bang grenades, tear gas, rubber bullets, helicopters, and armored vehicles, are routinely donated to local police departments by the Department of Defense. In fact, law enforcement received at least $760 million worth of military equipment from the Department of Defense between August 2017 and 2020.

These weapons paired with warrior training, which reinforces a mindset that treats civilians as potential enemy combatants, create a recipe for bloodshed.

A study on police violence showed that militarized police departments are more likely to kill civilians. Another study reports that militarized police units are usually deployed in communities of color and “contrary to claims by police administrators—provide no detectable benefits in terms of officer safety or violent crime reduction.”

The Hard Truth

There’s a massive gap between what America prepares its police officers for and what they actually do. They are trained to see themselves as warriors in combat against citizens, but in reality, only 4% or less of their time is actually spent responding to violent crimes.

The militarization of the police has become a dangerous amplifier for police violence. It is now tragically commonplace to read about unarmed Black men and women riddled with a multitude of police bullets. In fact, The Washington Post found 40% of unarmed people shot and killed in 2015 were Black. When people exercise their right to protest in response to police brutality, they are also met with excessive use of force.

In case you’re wondering if this is the standard cost of policing—it isn’t.

The U.S. police force kills its civilians at a higher rate than any other wealthy country in the world.

A Moment of Reflection

Our police force, local officials, and judicial branch aren’t the only ones responsible for the policing inequity. Biased news reporting, apathy from the public, and the casual weaponizing of the police force by individual citizens (hello, Amy Cooper) can also enable police brutality.

Think about a time you may have sat on the sidelines to an injustice or a moment when you “played it safe,” instead of speaking up.

How did your actions align with your values? How will you honor your values next time?

Extra Credit

Art has the power to provoke critical thinking. Dive into the work of artists like Hank Willis Thomas that push the conversation forward: