The Right to Kill

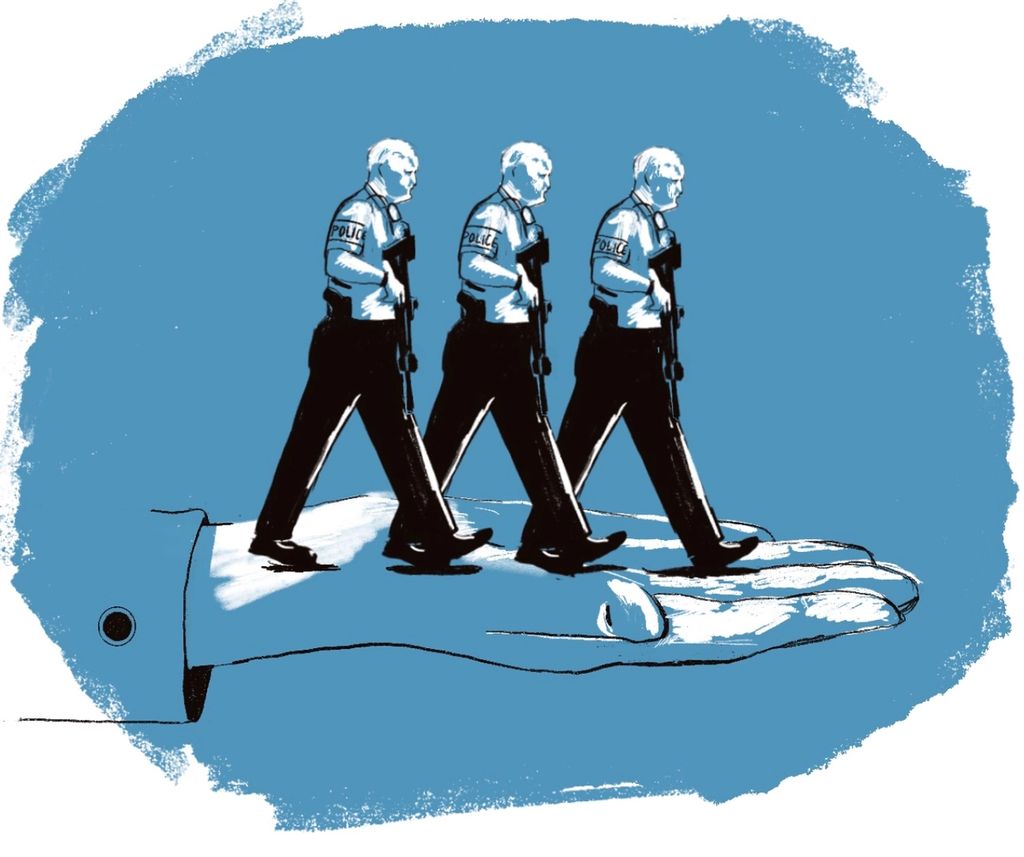

Colonies were the first to pass laws that allowed white settlers to kill or wound enslaved people. Examine how local laws and policies have shielded brutality ever since.

From the earliest days of American policing, laws have been written to preserve Black oppression. If you did anything perceived as breaking the rules around racial hierarchy, you could be punished with violence.

A critical part of ending police brutality is decoding how it has been protected under the law—so let’s get started.

1600s: Outlawing black “resistance”

In 1672, it was lawful “to kill or wound a slave who resisted arrest.” The word “resist” was interpreted loosely, which made it possible for anyone to kill a Black person. Lawmakers also ruled that owners of any enslaved person killed would receive money for the loss of property—even if it was the slave owner who made the killing.

This shielded white citizens, slave owners, and slave patrols from accountability and empowered them to hunt and kill anyone who tried to escape to freedom. It reinforced white control and alleviated any guilt or responsibility. If it’s legal, it must be okay... right?

It is important to note that that in many parts of the country like the south, civil rights, legal recourse and economic independence for the enslaved was out of reach. It wasn't just fear or violence that allowed people to remain enslaved. The parameters around legally seeking freedom created barriers to liberation. Many had to flee to other parts of the country like Maryland, New Netherland, New England, etc.

It was common for them to be captured by slave patrols. In the early 1700s the resistance law allowed slave owners to discipline slaves to death or, in some cases, to kill runaways without penalty.

1900s: Weaponizing “Probable cause”

This approach continued into the 1900s under a new guise: probable cause. In 1942, The Uniform Arrest Act was passed. It authorized policemen to "stop any person who he has reasonable ground to suspect is committing, has committed, or is about to commit a crime.” The law stated, “Any person so questioned who fails to identify himself or explain his actions to the satisfaction of the officer may be detained and further questioned and investigated.”

There’s danger in equating “reasonable” with “probable.” This act gave officers license to stop anyone for anything. And it became a real weapon for inequity, setting the stage for the “Stop and Frisk” laws established in the 90s. From John Smith in Newark to Rodney King in Los Angeles, probable cause has been used as a cover for merciless acts of brutality and harassment against Black people.

2000s: Spinning a web of protections

Does it ever feel like cops are above the law?

In most cases, they are. Of the 7,666 times U.S. police officers were charged with the unlawful murder of a civilian between 2013-2019, only 25, or 0.3%, resulted in a conviction.

1,881 officers

Today, a web of sophisticated protections exist to shield police, including police union contracts, purge clauses, and the qualified immunity doctrine.

How police unions enable a lack of accountability

Police union contracts, typically negotiated without public input, mandate how investigations into misconduct will be handled. This includes disciplinary measures, how investigations will be conducted, and ways officers can overturn or avoid accountability.

For example, in most states, the union contract prevents officers from being questioned in an investigation immediately after the use of force—even when the victim is killed. Officers are given a "cooling off period."

Compare this with how civilians are treated, who are typically questioned immediately after an incident to ensure they don't have the opportunity to change their story. This cooling off period, paired with the fact that some cops get access to preferential evidence in some cases, gives officers the ability to rehearse and carefully prepare their version of events.

Over 70% of collective bargaining agreements allow officers sanctioned for misconduct to appeal to an arbiter. The arbiter’s decision is binding and overrides the decisions and recommendations of supervisors, police officials and civilian review boards.

Purging away police misconduct

Purge clauses, also negotiated by unions, are another popular protection invoked by departments. This clause removes previous disciplinary actions against a police officer from their record over a period of time, usually two to five years, so they can’t be referenced in an investigation. Derek Chauvin received at least 17 misconduct complaints before he was charged for George Floyd’s death.

A lot of these protections are negotiated in the police bill of rights, used by 16 states. States that haven’t passed this law have created similar ones that include barring the public from accessing body camera footage and disciplinary records when reviewing misconduct. This blocks accountability and makes it challenging for victims, researchers, and journalists to document and share misconduct data with the public.

It’s ridiculous that I can’t tell you how many people were shot by the police last week, last month, last year.

Source: The Atlantic

Unpacking qualified immunity

“Qualified immunity is a judicially created doctrine that shields government officials from being held personally liable for constitutional violations—like the right to be free from excessive police force—for money damages under federal law so long as the officials did not violate 'clearly established' law.”

Source: Lawfare BlogThe qualified immunity doctrine was originally established to shield public officials who are performing discretionary functions from civil liability. But it’s evolved into a shield for police when officers are accused of violating the constitutional rights of citizens, like the right to be free from excessive police force.

After a constitutional violation that can’t be reversed, financial compensation is frequently the only way to obtain justice. Qualified immunity routinely makes it difficult for victims (or their families) from receiving financial damages from police officers.

How prosecutors protect police

In most jurisdictions, when it comes to securing convictions, the district attorney is the local official responsible for proving an officer’s guilt when they violate the law.

But they rarely do.

Police officers are critical to proving criminal cases. They gather the evidence and testify during trials. District attorneys aim to maintain a positive relationship with the police to do their jobs. If a district attorney convicts a police officer, the local police force may retaliate. For example, an officer may stop collaborating with a district attorney; as a result, this may jeopardize their working relationship with the police department. This can have a significant impact on their career.

Juries also play a role in unintentionally limiting accountability. They generally prefer not to question a police officer’s point of view and grand juries rarely indict them.

A fair and just system needs to be implemented where a District Attorney can prosecute a police officer fairly without fear of retaliation.

Source: The AtlanticWhat does it all add up to? An environment that protects badged perpetrators, shrugs off violence, and allows misconduct numbers to keep climbing.

A moment of reflection

Reflect on actions that were legal in the past that we consider completely unacceptable today.

The persecution of Jews used to be legal. Not allowing women to vote was legal. Not allowing Black people to read and write was legal. Banishing Japanese Americans to internment camps was legal.

Not allowing Native, Black, and Chinese Americans to testify in court was legal. Not allowing people to marry outside their race was legal.

How do you personally define justice and injustice in society? How does America’s current policing laws and enforcement approach measure up to your perspective?